Daily Archives: July 21, 2020

169. Wall plaque, from Oba’s palace.

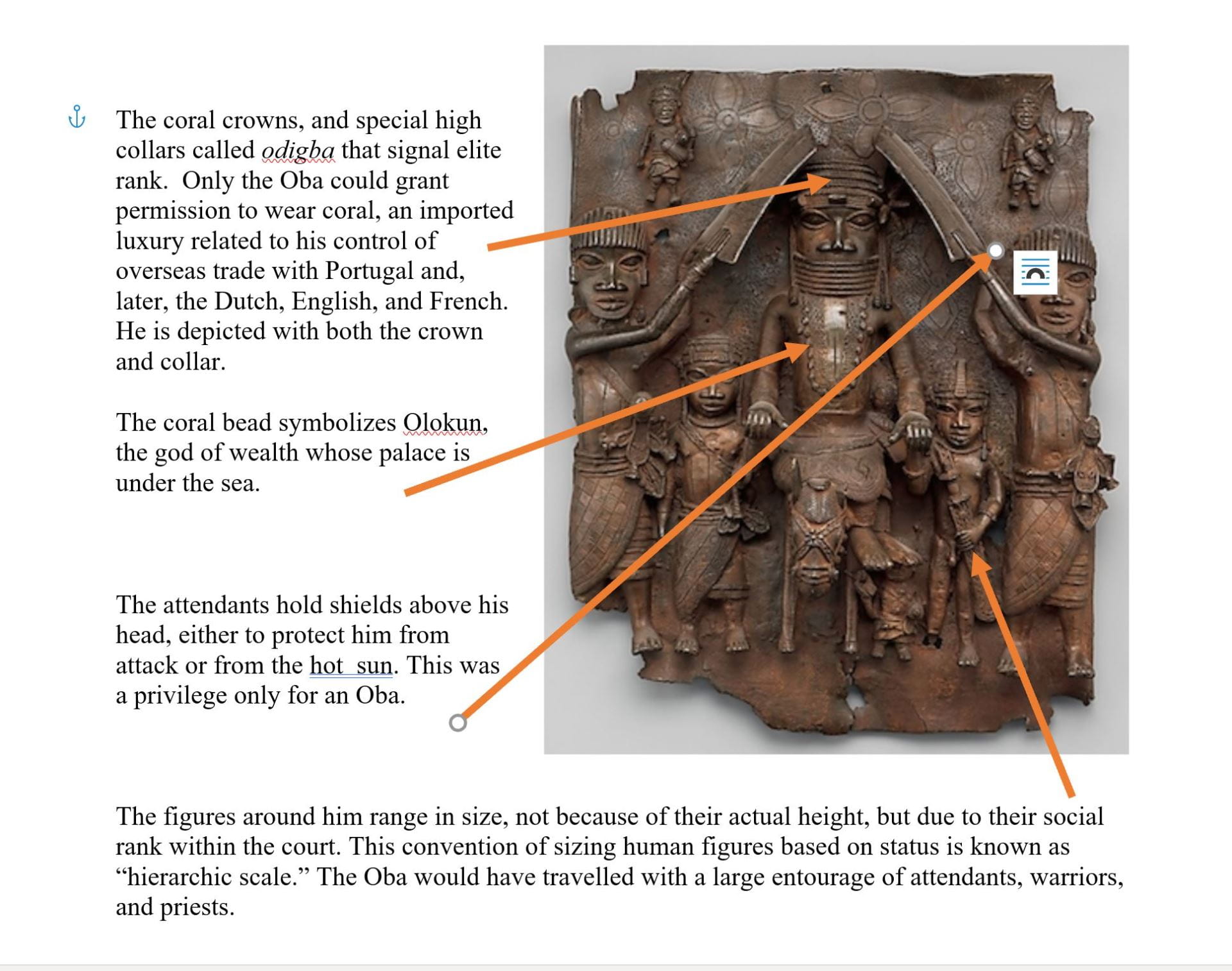

- Wall plaque, from Oba’s palace. Edo peoples, Benin (Nigeria). 16th century C.E. Cast brass. 14” x 15” in size.

The Benin kingdom, established in the 13th century, reached its peak of wealth and power in the 16th century. The kingdom was just west of the Niger River in west coastal region of Africa. Benin kingship was hereditary and considered sacred. The purpose of many of the finest artworks from Benin was to honor the ruling oba – the king – along with his family and ancestors.

The leaders of the kingdom of Benin trace their origins to a ruling dynasty that began in the fourteenth century. The title of “oba,” or king, is passed on to the firstborn son of each successive king of Benin at the time of his death. During the 16th and 17th centuries, a remarkable series of cast brass plaques were created to adorn the exterior of the royal palace in Benin City. A 17th century European visitor to the court of Benin described the sprawling palace complex—with its many large courtyards and galleries—as containing wooden pillars covered from top to bottom with rectangular cast brass plaques. These plaques are understood to have individual meanings but to also tell complex overall narratives in relationship to one another. The artists of such works were far more concerned with the communication of hierarchies and status than in capturing individual physical features.

These plaques conform to a convention of “hierarchical proportions,” in which the largest figure is the one with the greatest authority and rank. In this example, a warrior chief is in the center, flanked on either side by attendants and soldiers of lesser importance. Regalia and symbols of status are emphasized above all other aspects of the subject. For example, the warrior is shown with leopard-spot scar marks on his skin and a leopard-tooth necklace, which associate him with the stealth, speed, and ferocity of the leopard. As “king of the bush,” the leopard is one of the principle symbols of Benin kingship. Additionally, the warrior chief wears a coral-studded helmet and collar, a lavish wrap, and a brass ornament on his hip. In his left hand he carries a ceremonial sword, a gesture of honor and loyalty, and holds a spear in his other hand.

Citations:

Google Drive: Malady.APAH

Benin Plaque: Equestrian Oba and Attendants. (2020, July 21). Khan Academy. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/africa-apah/west-africa-apah/a/benin-plaque-equestrian-oba-and-attendants

167. Conical tower and circular wall of Great Zimbabwe

- Conical tower and circular wall of Great Zimbabwe. Southeastern Zimbabwe. Shona peoples. c. 1000–1400 C.E. Coursed granite blocks. 36’ tall max; 820’ extent of walls.

African art is as diverse as the continent itself is vast. Early civilizations of southeastern Africa date back to the Iron Age and began with the Shona people. Zimbabwe is actually a Shona term that means “stone buildings.” The early settlers of Zimbabwe arrived around 400 AD and began building the city of Great Zimbabwe around 1100 AD. At its peak the population of Great Zimbabwe was between 10,000 and 20,000 people, most living far away from the stone structures. These people survived through trade of gold, ivory, and exotic skins for porcelain, beads, and other manufactured items from coastal towns.

The ruins of this complex of massive stone walls undulate across almost 1,800 acres of present-day southeastern Zimbabwe. Great Zimbabwe was constructed and expanded for more than 300 years in a local style that embraced the design of flowing curves. Great Zimbabwe is set apart by the terrific scale of its structure. Its most formidable edifice, commonly referred to as the Great Enclosure, has walls as high as 36 feet extending approximately 820 feet, making it the largest ancient structure south of the Sahara Desert. Great Zimbabwe’s most enduring and impressive remains are it stone walls. These walls were constructed from granite blocks gathered from the exposed rock of the surrounding hills. All of Great Zimbabwe’s walls were fitted without the use of mortar by laying stones one on top of the other, each layer slightly more recessed than the last to produce a stabilizing inward slope. Early examples were coarsely fitted using rough blocks and incorporated features of the landscape into the walls. The walls are thought to have been a symbolic show of authority, designed to preserve the privacy of royal families and set them apart from and above commoners.

Citation:

Google Drive: Malady.APAH

161. City of Machu Picchu.

- City of Machu Picchu. Central highlands, Peru. Inka. c. 1450–1540 C.E. Granite (architectural complex).

Machu Picchu, the lost city of the Inca, is one of the most important archaeological sites in South America and the most visited tourist attraction in Peru. Despite being located close to the Inka capital of Cusco, the site was never discovered by the Spanish during their conquest, consequently it was not destroyed and remained relatively intact. Machu Picchu, meaning ‘Old Peak’ in the Quechua (ketch-wah) language, refers to the mountain that overlooks the city, its Inka name is not known. Believed to have been built by Pachacutec (Patch-uh-koo-tek), who ruled from 1438-1471 AD, the true purpose of Machu Picchu has never been conclusively determined. Although now it is believed to have been a retreat for the Inka chief and his elite or perhaps even a secret ceremonial city. Situated two thousand feet above the Urubamba River and invisible from below, the cloud-shrouded city contains palaces, baths, temples, storage buildings and around 140 houses, all in a good state of preservation. Spread over approximately 5 square miles, Machu Picchu housed a population of around 750 to 1200 people. It consists of a number of Sectors or Districts, which relate to the activities which were carried out there.

Also called the Temple of the Sun, this building’s purpose is echoed in its unique shape. It is composed of two main parts: an upper curved stone enclosure with windows and niches placed in it, and a cave beneath this structure with masonry additions that hold more niches. Modifications of the windows in the Observatory’s upper walls indicate that they were used to calculate the June solstice.

Intihuatana is a ritual stone with the astronomic clock or calendar of the Inca. inti watana is literally an instrument or place to “tie up the sun”, often expressed in English as “The Hitching Post of the Sun.” The stone’s name refers to the idea that it was used to track the passage of the sun throughout the year, part of the reckoning of time used to determine when religious events would take place and similar to the Observatory.

162. All-T’oqapu tunic. Inka

- All-T’oqapu tunic. Inka. 1450–1540 C.E. Camelid fiber and cotton.

Textiles and their creation had been highly important in the Andes long before the Inka came to power in the mid-15th century—in fact, textile technologies were developed well before ceramics. Finely-made textiles from the best materials were objects of high status among nearly all Andean cultures, much more valuable than gold or gems. The is an example of the height of Andean textile fabrication and its centrality to Inka expressions of power. The decoration of the tunic is where its name derives from. T’oqapu are the square geometric motifs that make up the entirety of this tunic. These designs were only allowed to be worn by those of high rank in Inka society. Individual t’oqapu designs appear to have been related to various peoples, places, and social roles within the Inka empire. Covering a single tunic with a large variety of t’oqapu likely makes this a royal tunic. 35” X 30”

Citations:

Google Drive: Malady.APAH

All-T’oqapu Tunic. (2020, July 21). Khan Academy. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/indigenous-americas-apah/south-america-apah/a/all-toqapu-tunic

160. Maize cobs. Inka.

- Maize cobs. Inka. c. 1440–1533 C.E. Sheet metal/repoussé, metal alloys.

This beautiful metal object is a gold-silver alloy corncob sculpture. It mimics the appearance of a ripe ear of corn breaking through its husk, still on the stalk but ready to be harvested. Approximately 11 inches long.

In this sculptural representation of maize, individual kernels of corn protrude from the cob that is nestled in jagged metallic leaves. Inka metalsmiths expertly combined silver and copper to mimic the internal and external components of actual corn. Hollow and delicate, the ears of corn on the stalk are life-sized. After the Spaniards arrived in the Andes, the European invaders soon desired the gold and silver belonging to the Inka. Some of the earliest Spanish chroniclers record the placement of a garden composed of gold and silver objects among many of the offering and ritual spaces in the Qorikancha. Pedro de Cieza de León describes a golden garden in his 1554 account – QUOTE:

“In the month of October of the year of the Lord 1534 the Spaniards entered the city of Cusco, head of the great empire of the Inkas, where their court was, as well as the solemn Temple of the Sun and their greatest marvels. The high priest abandoned the temple, where [the Spaniards] plundered the garden of gold and the sheep [llamas] and shepherds of this metal along with so much silver that it is unbelievable and precious stones, which, if they were collected, would be worth a city.”

After the defeat of Inka leadership in the 1530s, Spanish royal agents set up colonies across the continent. They looted Inka objects in large quantities and sent many back to Spain. The silver corncob and stalk were likely part of the spoils captured in this raid. The Inka commonly deployed small-scale naturalistic metallic offerings, like the silver alloy corncobs, in ritual practices that supported state religion and government.

Citation:

Google Drive: Malady.APAH

159. City of Cusco, including Qorikancha (Inka main temple)

INKA

The Inka civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century, and the last Inka stronghold was conquered by the Spanish in 1572. The Inka left no written history. Most of what is known of their culture comes from early Spanish accounts and archeological finds. Stretching 2,500 miles, the Inka Empire had a relatively short life of only about a hundred years. When the Spanish conquered the Inka, they were a small ethnic group based in Cusco, ruling more than 12 million people from 100 different cultures and speaking at least 20 languages. The Inka Empire was ruled with efficiency in part because of a superb highway system that included intermittently paved roads up to 24 feet wide, tunnels, bridges, and stepped pathways cut into living rock.

- City of Cusco, including Qorikancha (Inka main temple), Santo Domingo (Spanish colonial convent), and Walls at Saqsa Waman (Sacsayhuaman). Central highlands, Peru. Inka. c. 1440 C.E; convent added 1550–1650 C.E. Andesite.

The city of Cusco dates to 1200 AD and its main period of expansion occurred in the 15th century. Cusco was the capital of the Inka Empire from the 13th century until the Spanish arrived although it was an Inca rebellion in 1536 which led to its destruction and to its eventual rebuilding by the Spanish. This started a cultural mix that left its imprint on every aspect of Peruvian culture, something that is especially noticeable in Cusco. One of the most interesting things about the architecture of Cusco are the early Inca walls constructed of enormous granite blocks. The blocks are shaped to fit together perfectly in a puzzle pattern and laid without the aid of mortar. The architecture of Cusco has survived numerous earthquakes.

Cusco, which had a population of up to 150,000 at its peak, was laid out in the form of a puma and was dominated by fine buildings and palaces, the richest of all being the sacred gold-covered and emerald-studded Qorikancha complex which included a temple to the Inca sun god Inti. According to writings of the Spanish, the walls of the temples were covered with gold plate, which were looted shortly after the Spanish arrived in 1533. The whole capital was built around four principal highways which led to the four quarters of the empire. The city was also laid out in the form of a puma. The Qorikancha was the physical and spiritual heart of Cusco–it represented the heart of the sacred panther outline on the map.

“The complex layout has been compared to the Temples of the Sun at Llactapata and Pachacamac: in particular, although this is difficult to pin down given the lack of integrity of Qorikancha’s walls, Gullberg and Malville have argued that the Qorikancha had a built-in solstice ritual, in which water (or chicha beer) was poured into a channel representing the feeding of the sun in the dry season.” (Thought Company)

Looted in the 16th century soon after the Spanish conquistadors arrived , the Coricancha complex was broken down and converted in the 17th century to the Catholic Church of Santo Domingo on the top of the original Inka foundations. What is left of the complex is the foundation on the sun temple, part of the enclosing wall, some of the Chasca (stars) temple, and a few stones of the others.

“Sacsayhuaman” is a Quechua word that “Saqsay”=”Saciarse” and “Huaman”=”Halcon”, which means “The place where the hawk is satiated”. The fortress of Sacsayhuaman was one of the largest architectural structures created by the Inkas. It began during the government of Inka Pachacutec (the ninth Inka) and later was continued by his son Tupac Inca Yupanqui and later finished by Huayna Capac around the 15th century.

Sacsayhuaman served as an important military fort of the Inka empire. It was built on a rocky promontory on the northern access point to the city of Cusco, and it is here that the Inkas stored their weapons and were prepared for invasion. The first structures were made using only mud and clay. Subsequent rulers then replaced these with magnificent stonework. The walls used huge finely-cut polygonal blocks, many over 4 meters in height and weighing over 100 tons.

Historically, in the pampas of Sacsayhuaman, the “Inti Raymi” takes place, or the “Party of the Sun”. on the 24th of June, at the winter solstice, the Inka offered a sacrifice to the sun god, Inti. The ceremony is still practiced in Cusco.

Citations:

158. Ruler’s feather headdress (probably of Motecuhzoma II). Mexica (Aztec)

- Ruler’s feather headdress (probably of Motecuhzoma II). Mexica (Aztec). 1428–1520 C.E. Feathers (quetzal and cotinga) and gold.

VIDEO

Moctezuma’s headdress is a featherwork crown which tradition holds belonged to Moctezuma II, the Aztec emperor at the time of the Spanish Conquest, In 1519, when Spanish ships reached the shores of what is now Mexico, they encountered the thriving Aztec Empire. Initial contacts were friendly, but soon Hernán Cortéz and his conquistadores vanquished the empire and took Emperor Moctezuma II prisoner. Countless artifacts were sent to Europe. The most magnificent is the early Mexican feather head-dress known in Mexico as “Penacho”. Did this feather head-dress really belong to the legendary Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II? Today, many myths and legends are still linked to this magnificent artifact.

It consists of over 450 tail feathers of the Resplendent Quetzal (BL), as well as feathers of the Lovely Cotinga (BR), Roseate Spoonbill (TL), Squirrel Cuckoo (TR) and additional shorter feathers of the Quetzal. They are mounted on a net of vegetal fibers and wooden sticks. The front part is decorated with gold ornaments. In its original state, a golden bird’s beak was attached to the headdress. Upon its discovery the headdress was restored, feathers and metal ornaments (now of gilded bronze) were substituted. The approximate measurements of the feathered piece are 45 inches in height and a width of 68 inches.

Citation:

157. Templo Mayor (Main Temple).

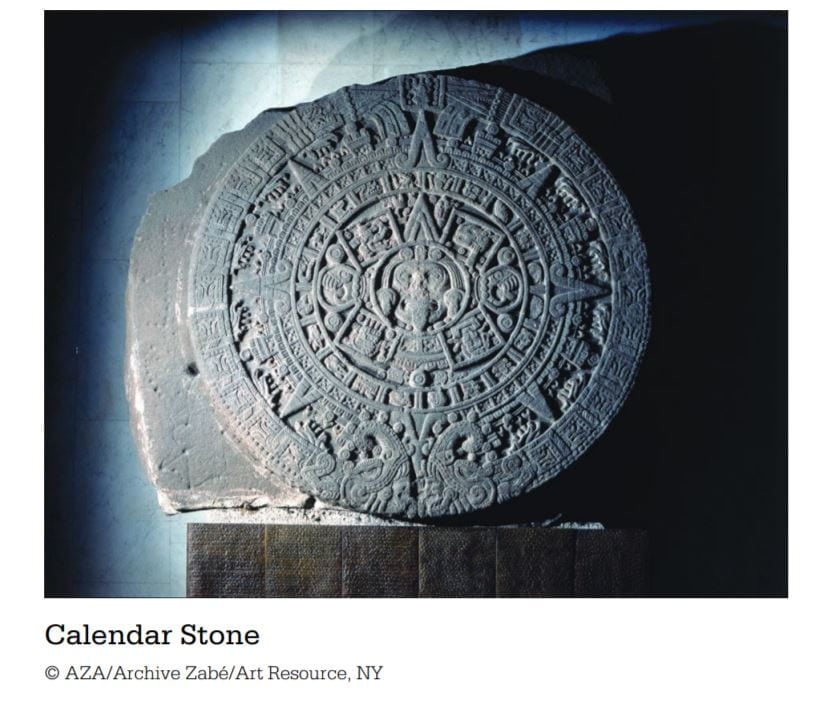

157. Templo Mayor (Main Temple). Tenochtitla`n (modern Mexico City, Mexico). Mexica (Aztec). 1375–1520 C.E. Stone (temple); Volcanic stone (The Coyolxauhqui Stone); Jadeite (Olmec-style mask); Basalt (Calendar Stone).

The Templo Mayor or Great Temple dominated the central sacred precinct of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. Topped by twin temples dedicated to the war god and the rain god it was a focal point of the Aztec religion and very center of the Aztec world. It was also the scene of state occasions such as coronations and the place of countless human sacrifices where the blood of the victims was thought to feed and appease the two great gods to whom it was dedicated. The Templo Mayor was the most important structure at the center of a large sacred precinct measuring 1,200 ft on each side. The precinct may have contained as many as 78 different structures but the Templo Mayor was by far the tallest and must have dominated the city skyline. The temple was actually a 180 ft high pyramid platform with four tiers and two flights of steps on the western side leading to a summit with two twin temples or shrines, the whole structure being faced with white lime plaster and brightly painted. The rain god – called Tlaloc – was also associated with mountains and it is probable that the Templo Mayor was conceived as a literal architectural mountain in homage to this facet of the rain god, a man-made imitation of the so-called “Mountain of Sustenance.”

COYOLXAUHQUI STONE

COYOLXAUHQUI – COY-OOL-ZAH-KI

The Coyolxauhqui Stone is a carved, circular Aztec stone, depicting the mythical being Coyolxauhqui dismembered and decapitated. It was rediscovered in 1978 at the site of the Templo Mayor. Coyolxauhqui was the Aztec goddess of the Moon who was famously butchered by her brother Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, in Aztec mythology. Coyolxauhqui, whose name literally means “Painted with Bells,” was the sister of Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of war and patron god of Tenochtitlan. Coyolxauhqui upset Huitzilopochtli when she insisted on staying at the legendary sacred mountain. The god of war grew angry and then decapitated his sister and then ate her heart. He then threw her body down the mountain, at which point her body broke apart. The myth may relate to the battle the moon fights with the sun each night. The myth of Coyolxauhqui’s demise was commemorated in a large stone disk, which was excavated at the base of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan. It depicts in high relief the dismembered and decapitated corpse of Coyolxauhqui. The goddess wears only a warrior’s belt with skull, a headdress with eagle down feathers, and a bell on her cheek. Originally painted and carved in low relief, the Coyolxauhqui monolith is approximately eleven feet in diameter.

OLMEC MASK FOUND AT TENOCHTITLAN

Over a hundred ritual deposits containing thousands of objects have been found associated with the Templo Mayor. Some offerings contained items related to water, like coral, shells, crocodile skeletons, and vessels depicting the rain god Tlaloc. Other deposits related to warfare and sacrifice, containing items like human skull masks with obsidian blade tongues and sacrificial knives. Many of these offerings contain objects from faraway places—likely places from which the Aztec collected tribute. Some offerings demonstrate the Aztec awareness of the historical and cultural traditions in Mesoamerica. For instance, they buried an Olmec mask made of jadeite. The Olmec mask was made over 1500 years prior to the Aztec, and its burial in Templo Mayor suggests that the Aztec found it precious and perhaps historically significant.

About 4 inches by 3.5 inches in size.

CALENDAR STONE

The Sun Stone, or Calendar Stone as it is sometimes called, is perhaps the most famous work of Aztec sculpture and likely dates after the year 1250. It is almost 12 feet in diameter and weighs about 24 tons. At the center is the face of the solar deity, Tonatiuh (toe-nah-tyuh), carved in relief. There are symbols surrounding that represent previous eras and symbolize the movement of time. The exact meaning and purpose of the stone is unclear. It is likely to have been used in some kind of religious ritual but the various symbols that represent days, weeks, and months seem to have a chronological or even astronomical purpose. It is a fascinating and complex work of sculpture. Whatever it may have meant in its original context, it is a work of art that shows the technical abilities and virtuoso skills of the artist who made it.

Citations:

Google Drive: Malady.APAH

#155 Yaxchilán

#155 Yaxchilán. Chiapas, Mexico. Maya. 725 C.E. Limestone (architectural complex).

Yaxchilán is a classic Maya urban complex – Its architecture is covered with hieroglyphs and extensive relief sculpture. Yaxchilán thrived between A.D. 500 and 700. Famous for its more than 130 stone monuments, among which include carved lintels and relief sculptures depicting images of royal life, the site also represents one of the most elegant examples of classic Maya architecture.

The heart of Yaxchilan is called the Central Acropolis, which overlooks the main plaza. Here the main buildings are several temples, two ballcourts, and one of the two stairways filled with reliefs. Located in the central acropolis, Structure 33 represents the apex of Yaxchilán architecture and its Classic development. The temple was probably constructed by the ruler named Yaxun B’alam IV – also called Bird Jaguar #4 – or dedicated to him by his son. The temple, a large room with three doorways decorated with stucco motifs, overlooks the main plaza and stands on an excellent observation point for the river. The real masterpiece of this building is its nearly intact roof, with a high crest or roof comb, a frieze, and niches. The second hieroglyphic stairway leads to the front of this structure.

Roof comb (or roof-comb) is the structure that tops a pyramid in monumental Mesoamerican architecture. Roof-combs crowned the summit of pyramids and other structures; and they consisted of two pierced framework walls which leaned on one another. This framework was covered by plaster and decorated with artist depictions of gods and/or important rulers.

Structure 33

Temple 23 is located on the southern side of the main plaza of Yaxchilan, and it was built about AD 726 by the ruler Itzamnaaj B’alam III – also known as Shield Jaguar the Great – the son of Yaxun B’alam IV – Itzamnaaj B’alam III ruled 681-742 AD. It was dedicated to his principal wife Lady K’abal Xoc. The single-room structure has three doorways each bearing carved lintels, known as Lintels #24, #25, and #26. Lintel 24 is the easternmost of three door lintels above the doorways in Temple 23, and it features a scene of the Maya bloodletting ritual performed by Lady Xoc, which took place, according to the accompanying hieroglyphic text, in October of 709 AD. King Shield Jaguar the Great is holding a torch above his queen who is kneeling in front of him, suggesting that the ritual is taking place at night or in a dark, secluded room of the temple. Lady Xoc is passing a rope through her tongue, after having pierced it with the spine of a stingray fish, and her blood is dripping onto bark paper in a basket. The textiles, headdresses and royal accessories are extremely elegant, suggesting the high status of the figures. The finely carved stone relief emphasizes the elegance of the woven cape worn by the queen. The king wears a pendant around his neck portraying the sun god and a severed head, probably of a war captive, adorns his headdress.

Lintel 25 from Structure 23 depicts a scene from a bloodletting ritual and conjuring event. Hieroglyphic inscriptions describe that the ritual was performed by Lady Xoc – it portrays Lady Xoc making contact with a spirit who emerges gripping a spear from the open jaws of a vision serpent. This serpent has been called forth by the blood sacrifice of Lady Xoc. In her left hand, Lady Xoc holds a bowl or a basket that contains instruments of bloodletting as well as bloodied bark paper. A similar object is placed on the ground before her. This also contains bloodied bark paper and from it rises the vision serpent. Lady Xoc is dressed in an ornately patterned costume trimmed in fringe and pearls, as well as a Sun God pectoral, jade wristlets, and an intricate headdress whose form seems to suggest aspects of the vision serpent before her. This elaborate attire reflects the ceremonial nature of her actions. Blood scrolls are carved on her cheek near her mouth, reflecting the bloodletting that she had performed in Lintel 24, the previous lintel in the series, also found in Structure 23.

Lintel 25 and the series to which it belongs were originally found placed above the central doorway of Structure 23. These lintels depict scenes from intimate bloodletting rituals and conjuring events performed by the elite in dark, sacred spaces like the interior of Structure 23. Inscriptions presented through glyphs on both Lintel 24 and Lintel 25 identify the date of this particular bloodletting ritual as October 28, 709 C.E., and they note that the purpose of the ritual was to mark the anniversary of Shield Jaguar’s ascension to the throne in October 681 C.E.

The smoke, pain, and possible ingestion of hallucinogens produced conditions favorable for the conjuring of a vision serpent. Bloodletting was a form of sacrifice that was expected of Maya rulers and was particularly associated with ceremonies of renewal and rebirth. The Maya believed that their gods sacrificed their own divine blood to create humankind. In return, the Maya were expected to make blood sacrifices to the gods to maintain the order of the universe. Bloodletting, or sacrificing one’s own blood, was one way to achieve this. This bloodletting ritual was performed most dramatically by members of the royal family, but it was also performed by other Maya elites and religious leaders. Bloodletting took place at every major political and religious ceremony because it was the means by which the gods or ancestors could be “present” to sanctify the event. “Present” is meant literally in this case: the Maya believed that the act of bloodletting opened a portal to the Other World through which gods and spirits could pass, as depicted in Lintel 25. Bloodletting rituals connected Maya royals to the sacred sphere and legitimized their social and political positions as divinely sanctioned rulers. On Lintel 25 the central role played by Lady Xoc in this bloodletting ritual would have legitimized Shield Jaguar’s reign and reinforced her power as his primary wife and queen. Lintel 25 demonstrates that Lady Xoc held enormous political and spiritual power during the reign of Shield Jaguar. It is possible that she commissioned this series of lintels, which would be a rare example of female patronage, and by extension female power, in Maya art.

Bird Jaguar IV also had Structure 40 built as part of his political campaign to secure his rulership. Structure 40 displays the typical Yaxchilán architectural style—a rectangular vaulted building with a stuccoed or plastered roof comb. Like many other Yaxchilán buildings it had stele associated with it, such as Stela 11 that showed Bird Jaguar IV towering over war captives accompanied by his parents. The stela, like the buildings and other commissioned works, were intended to advertise Bird Jaguar IV’s dynastic lineage and thus his right to rule. (Smart History)

Citations:

Google Drive: Malady. AP Art History

The British Museum, “Maya: The Yaxchilán Lintels,” in Smarthistory, March 1, 2017, accessed July 21, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/maya-the-yaxchilan-lintels/.